*This talk was presented at the Ruby Conference 2015 in Kiev, Ukraine.

Introduction

Technologists hold the keys to the most powerful force in the modern world, but recently they’ve forgotten not only how to wield it, but that they own it. It wasn’t so long ago that technology represented hope; that it represented power; and, most of all, that it represented change. Our hacker culture has settled, and it now accepts meaningless goals, meaningless rewards, and meaningless lives.

We are living at the precise moment when, for the first time in history, the planet is connected at a practical and personal level via a network of hyper-intelligent software and hyper-intelligent hardware. We live our lives during the very moment at which individuals possess the greatest power to affect change that they have ever held in the history of mankind.

A tipping point may already have been reached. Like the printing press, the radio, and the television before it, the makers of the internet may have already given away the deep knowledge to those that seek only the consolidation of wealth and control.

But, it may not be too late. The massive proliferation of knowledge and the flattening of understanding presents a unique opportunity for those of us currently piloting the spaceships: we can choose to continue patrolling the planet and maintaining the status quo, or we can choose to look over our shoulders - to the left - at a that glimmering light in the distance, and set a new course.

THIS IS THE POINT AT WHICH YOU SHOULD CAFFEINATE AND READ THE (EDITED) TRANSCRIPT BELOW.

My name’s Ara T. Howard. I run a small boutique software agency. We build all fashion of applications that touch the Internet – mobile, web, big data – in support of impact companies. Our definition of impact is companies who are working to create world where no one is limited by circumstance. It doesn’t necessarily mean it’s all for social good, or that it doesn’t make money, but it’s just trying to level the playing field for all people on the planet - very broad definition.

I’ve been in the Ruby community for a very long time – since before Ruby 1.4 – long before Rails - and I’ve seen Ruby go through some profound changes. One of these changes is how the development community at large, and Ruby in particular, has become a little bit more small minded than they were initially.

I’m going to encourage you to consider that a lot of the things we talk about, we obsess about, we think about may actually be the wrong things, and really to try to remind people that programming is a super powerful thing and that everyone in this room actually has a big responsibility to do something with that power.

I want to start out by asking – a show of hands – how many people think the world economy would not collapse in three days if every software developer in the world stopped going to work? No hands. So, this is what I’m talking about and yet, most of us aren’t working on changing the world for the better.

So, I’ll illustrate this with a story. I’m the guy in the middle – always the Linux guy. I’m going to start out with Ruby Conf. 2006, which was in Denver. At this Ruby conference I was still on a Linux lap top and what I witnessed was, in retrospect, a little bit of the beginning of the end. At that time I never had a Windows machine. I came from the Linux hacking community where there was really a deep belief at that time that through open source and through software we could actually change the world. Right? Code had power. There was this deep, revolutionary belief in what we were doing.

And this, I believe, was the moment when that began to change in a majority of developers minds. I think this guy on the left is the problem. I have one of these now. But I remember sitting there at Ruby Conf. and this guy had a Mac. It was the first Macbook. DHH was speaking at this Ruby Conf., and I remember it was like the first time where Ruby programming had this aura of being cool. It wasn’t just about making computer programs, it was not just about trying to change the world through open source, or being nice, or any of those things. It was also cool for the first time. And I remember thinking to myself, “Man, I fucking want one of those computers.”

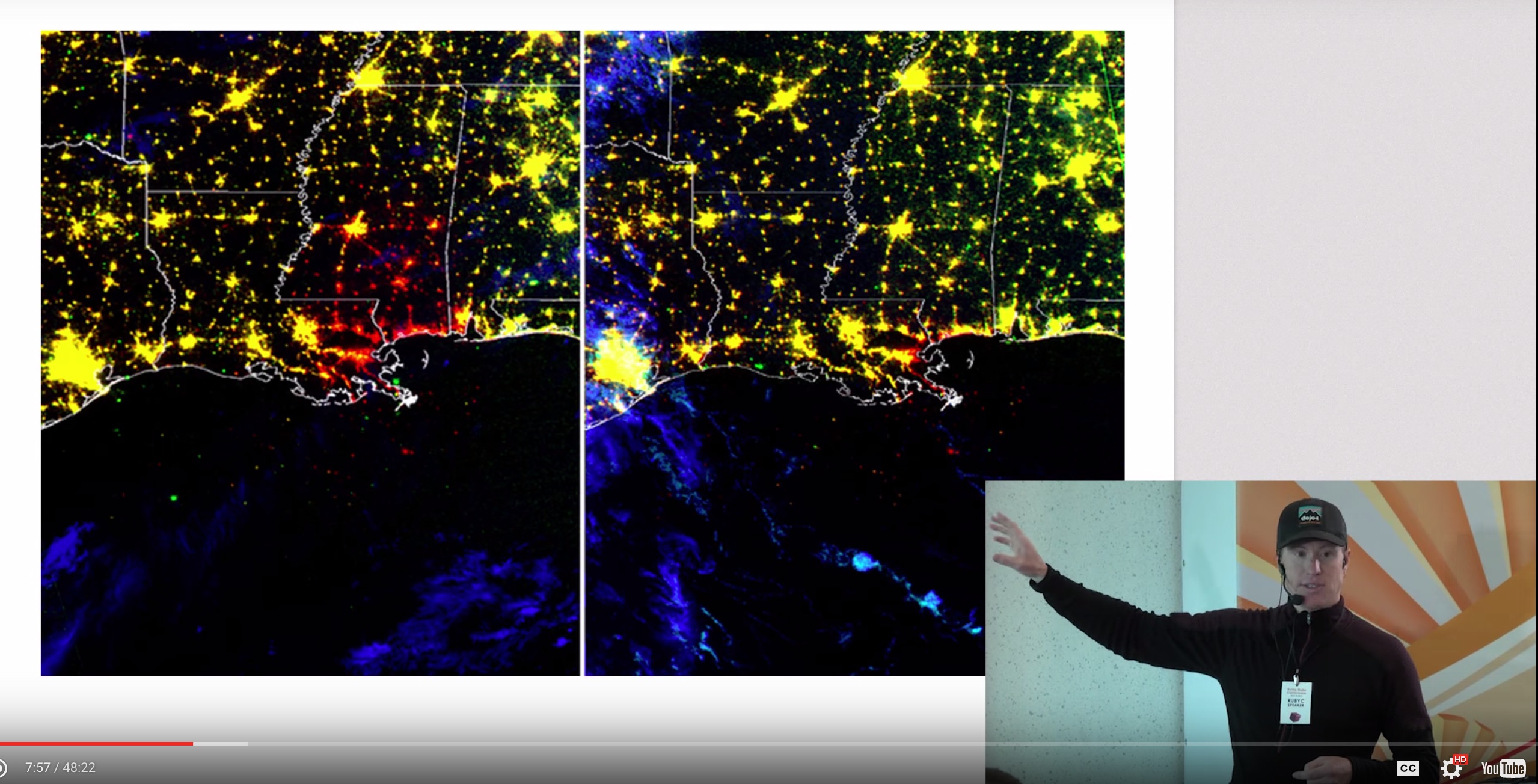

So, at the time I was working for a research faculty at The Cooperative Institute for Research in the Earth Sciences. I was helping to build what was the largest super computers in the world at that time (for five days or something until it was eclipsed). And after that I was doing some really cool Ruby work – also super computing work and big data - truly big data, as in Petabytes of data - visualizations and analysis with Ruby, which was kind of groundbreaking at the time.

The data came from a set of polar-orbiting satellites, which produce the only remotely-sensed data set that measures man. These DMSP satellites continuously collect data all over the world and it’s used for real-time tactical air decisions by the U.S. Air Force. It has the cool property, however, that on the backside of the world – the dark side – they just chuck that data.

My group was the official archive for this data, so we got a ton of money for doing some stuff I still don’t feel that great about. But what we did on the side was a little bit of a Robin Hood play, where we would take the discarded information and we would do things like be able to measure the extent of the storms after Hurricane Katrina for the White House. We would do things like measure the location of refugee camps in the Saharan desert so that food drops could go in but not reveal the location of those refugee camps to the opposing side so that they could be bombed. Or we would measure the total CO2 emitted into the atmosphere by gas flares, which by the way, is actually equivalent to like all the gasoline burned in cars per day. So, we felt kind of good about that and I felt like I was making a positive contribution - robbing from Peter to pay Paul, but it was a fun time.

But there was that fucking Mac laptop. I think by the time Ruby Conf. 2007 rolled around, it was really just about these two guys, right? Steve Jobs & Bill Gates and no one was really thinking about Linux in the Ruby community anymore, or really that sort of zeitgeist. We were hooked.

About this time I was contacted by what now is known to be a startup that was acquired by Oracle to compile the Gnu scientific library so that it would run in the Ruby one-click installer. And that was where I took the bait, basically. I quit my job and I started contracting. It was really cool. Looking back now realize that I was helping to build many of the startups that have been acquired in Boulder ever since. I was part of the machine.

So, yeah, I was drinking the Kool-aid. I was fully hooked and engaged in doing something that I now question with some suspicion. I made a lot of money, met a lot of people, super fun. I was able to start a company - DOJO4. We live in a fantastic place. Boulder’s amazing. We have super cool people. We enjoy what we do. It’s kind of cake, right? So it seems like everything should be good…

But I started getting this nagging sensation that I wasn’t really compelled by the work that I was doing. I started at night laying there thinking, “Man, do I really have to fucking build that same user system again, that same voting system or that same feature that every startup has?” Everything started seeming very much the same. It started feeling very incestuous and without purpose.

So we started having these discussions internally in the company, beginning of last year. Everything’s great but why are we doing this? Is it worth it? Should we do something else? And software’s hard, so these are important questions to ask. It’s not like it’s an easy job or a stress-free job. We started really wanting more.

So, this guy was also in the back of my mind at the time. How many people know who this is? [Hands go up] That’s fantastic. I gave this talk in a room of 300 people two weeks ago in Denver and I asked that same question and zero people raised their hands. It was shocking to me.

This is Richard Stahlman, and when I was a Linux hacker he wrote a lot of Manifestos. He’s a crazy motherfucker, for all intents and purposes. At the time he seemed genuinely crazy - he was talking about things like why open source software is important for things like privacy and why it could be a force to fight against government surveillance of your communications, just as an example. Everyone thought he was crazy.

So, this spider sense was ringing in my ear. If you go back and read some of the things he was saying, what you will discover is it was all fucking right. Every single thing was right. He may have not been the best messenger - it wasn’t candy-coated, perhaps it wasn’t sexy enough, it didn’t come wrapped with a little Apple icon on it, it wasn’t aluminum and there was no stock options. However, everything he said was right, and I think people have forgotten it. No one talks about freedom anymore in software.

In fact, we know now that simple decisions like the ones people in this room make such as contributing to open source software so that we have cryptography libraries that aren’t controlled by governments or corporations are kind of important - incredibly important, actually, and affect millions of lives.

So these things are rumbling around in my head – Stahlman, what the fuck are we doing? What are we making? Same thing over and over. Then I got invited to a conference that was hosted by The Unreasonable Institute. Now, they don’t have anything to do with software. They’re an accelerator, an incubator. They’re the one whose definition of impact I co-opted: A world where no one is limited by their circumstance. Their whole mission is to facilitate that revolution, and their whole belief is that governments can’t do it, NGOs can’t do it - only businesses can do it.

So this is not about charities, it’s not about legislation. The idea is that business can solve the world’s problems. I think a lot of times in software we think about a very bifurcated concept between donating our time to open source, to work for free for charities, to have hackfests to help our cities; and then we work to make money doing shit that a lot of us might not care about that much. So using business as a force for good is a really new idea and it took a long time for me to actually accept it.

So, I was a technical mentor at this two-week Girl Effect Accelerator. We worked seventeen hours a day. It was insane. We were working with 10 companies that were selected because their product directly had a positive impact on adolescent women. I won’t go into the details of why that was, but I will tell you that none of the companies were doing anything that you think that they might be doing.

For example one of them is a banking application – mobile banking. What the fuck does that have to do with adolescent women? Well, if you happen to be building that application in a country where 85% of the population has no access to banking, and the primary way of moving cash is to give kid the money and have them get on a bus – that happens to be a pretty dangerous job. Then you’re having an impact on women.

Or, you make solar lights. How does that impact adolescent women? Because in the countries that this company is operating in, women have less opportunity to do homework, they’re expected to do the cleaning and cooking, and by the time they would have an opportunity to do their homework it’s dark. They have no electricity so they can’t do their homework.

I thought, hey that’s neat; it’s great that they’re doing that. But then some other things started creeping in. Like, in two weeks working with ten startups no one said the word “exit” once. All the companies that we were working with – and these are companies that are operating in a place where the average consumer makes less than $2 per day. Poor countries. All these companies have profit revenues of 2.5 million or higher, so respectively they’re fucking killing it.

All the companies were bootstrapped and on a smooth revenue curve. No one was like, “We’re gonna take a bunch of cash, we’re gonna make up a problem, we’re gonna solve it and then as soon as we can just figure out the business model to do with this billions of dollars of software and data, we’re gonna be rich!” These folks didn’t take the money. They were selling their product out of the gate. Huge, huge technical innovations, right?

And the barriers that these companies face are things like: I’m selling a light but nobody has enough money and no way to pay me. So, in addition to making a light, I have to design a micro-finance company, I have to build an app that runs on feature phones (remember the little LCD screens before smart phones?) and smart phones, so that people can pay me in little bits. Oh shit, the local currency doesn’t work so I actually have to figure out how to do it with bitcoin and other ways of arbitrage so it can go across countries. So, every company had significant problems that we don’t have - like I can pay anybody here with a phone or cash, I can communicate with you, you have light - and they were solving a lot of these problems through technology.

This is possible because just in the last few years essentially you have an entire continent – and this is true elsewhere, Africa is just an example of this – where you have a shit-ton of problems, and everybody now has the Internet in their pocket. Right? And a Javascript engine.

So, this is a profoundly important time where if you write a piece of software, you have the ability to impact the entire world on this [holds up a phone]. That didn’t exist before right now. The tipping point’s here, today, right? With mobile phone ownership the opportunity is immense.

So, what I realized after digesting all this and working with all these companies was: whoa, this is actually working. They’re making money. They’re doing something that doesn’t suck. They’re doing incredibly cool technology. The engineering team is having fun. I mean, these are real challenges, right?

So, super interesting problem and ability to make an impact. And then I finally understood and developed a new definition of the word impact: if you have a fucking problem and I solve it, you buy it from me. You don’t need marketing for this. Some people just call this good business.

So, I think the thing that’s wrong with a whole lot of the startup community - and the development community by side effect – is that people have forgotten that the fundamental criteria for having a successful business and engineering a solution is having a real problem. Right? You actually need a problem to solve in order to write code that has an impact. And the whole point of this talk, again, is just to encourage the people on the ground – you, the troops – that this is possible.

There are plenty of real problems. We don’t have to be solving non-problems with one of the most powerful tools on the planet - code. So, why are we solving non-problems with it? To make people more money? Of course we want to make enough money, but we’re not smart enough make another choice or have an positive impact through our life’s work?

So, what my company did when I came back from that is we talked about it for quite awhile and then we fired everybody. Absolutely everybody. It wasn’t as harsh as it sounds. I actually talk with all our engineers, all our designers and all of our contractors and I said, “We’re tired of building stupid shit.” The sentiment when I started talking with everybody was that we all want to do something meaningful. Every single person said some permutation of, “That sounds great, because I’m tired of building stupid shit, too.”

So, we made some fundamental changes to our business model. Almost all the people that we fired are back in different capacities. We have a different organization now, but we jumped with both feet.

We also became a B Corp, which is fundamentally the equivalent of fair trade coffee or organic certification for food. There are 1,300 B Corporations in the world that are basically committed to business transparency, having a social impact. It’s about making money, but it’s also a commitment to making a positive impact on the world – socially, environmentally, etc. So, we’re still a software agency, and now have companies calling us up out of the blue saying, “You’re a B Corp, we’re a B Corp, we’re trying to solve this problem together.”

There are a lot of unknowns, we don’t know where it’s going to go long-term, but we’re all sleeping a lot better. We feel better about the work that we’re doing – still software, we’re still like fucking debugging javascript in IE. I mean, it’s the same job but something’s fundamentally different, and that’s real nice.

So, what I’m trying to engage people to think about is to come along on this journey with me. Think about what you’re doing and how you can do something a little bit better with the power that you have.

So, this may seem like a little bit high-level, un-actionable, abstract for somebody who’s going to go to work tomorrow morning at 9:00am. So, I just want to give three concepts for how you might start putting this into practice; and to encourage you to believe that it may actually have a bigger impact than you would think.

The first thing is just to position yourself to actually find real problems. So, does that mean quitting your job and like going to India or something? That’s not what I mean, actually. I think very few of us don’t have real problems within a two-mile radius of where we work or where we live. Does it mean working for charity, volunteering your time? It might.

One of the things that we do at DOJO4 is we’re on the Board of Awesome Boulder, which gives $1,000 a month to things that are 1) Awesome and 2) In Boulder. Sometimes they resemble charities, sometimes they resemble public art projects, but one of the things that’s really interesting about that from a software perspective is that just by being engaged in that I see a lot of things that I don’t see otherwise.

So, I think the value in getting engaged in some sort of volunteer work or charity is not just what you’re doing with your time, it’s that somebody will show you what the real problems for free. They’ll just tell you what the problem is. You don’t even have to be that creative. Oh, and by the way, you know how to use computers, so take the solution they’re working on and where they could turn it up to 2, you can turn it up to 2,000. Right? That’s the power that you have with computing.

Another way to find problems is to look at what’s painful for you, right? Like, what do you hate? I was saying earlier that I’ve written 100, 200 gems, something like that. One of my most popular gems of all time was a gem called rubyforge. This was before Ruby gems existed and it was the only way you could publish shit. It was so awful. You had to click all these buttons, and at some point I was like, really? I have to do this every time just to give somebody my code? So I automated it. I built a robot. I think it’s still my most popular gem of all time. I just looked at something that sucked for me, and I fixed it. If you hate doing something you can be guaranteed that a lot of other developers also hate doing it, too, so fix it and then move on to doing something bigger with your time. You’re having an impact, you’re letting somebody focus on something better than what they were focusing on before.

Another way to find real problems is to look at your group’s pain. In other words, looking at the opportunity in your work for being a little more human. Like, it’s actually hard to present something you’re unsure of, especially in a group of engineers who are always right. It’s maybe not that comfortable, right? Maybe you can have an impact there just in yoru cultural practices in the office. And you can extend that to your company and the users of your product. You can start to think about what’s painful for them and maybe taking the initiative, proposing something.

Number two is to position yourself to understand people. This is a big topic, but I think it’s really interesting. How many people here when they went to computer science school officially or unofficially were trained in psychology? I think this is interesting point because as engineers we all are told that the first step to solving a problem is understanding it, right? Ironically, the way that you understand a problem is by talking to people. Step 1. And it’s something that engineers have zero training in.

How do they know they’re solving a real problem if they can’t unpack it? We all know this, right? Like, business people are really bad at saying what their problem really is, but we have a responsibility to be better at trying to get at what they’re saying. Why are they saying it?

Two other quick points on positioning yourself to understand people. 1) I recommend looking for opportunities to break things. We use our intellect a lot, our technical skill. But look for opportunities to break your mind, think in new ways. I’ll make two specific recommendations. I recommend that you read What Makes You Not a Buddhist - because it’s a fascinating look at how our minds work, not because you may be interested in being a Buddhist.

I also recommend that you look at Gödel’s theory of incompleteness, which is foundational to computer science. I am going to also lead you down a rabbit hole of questioning the things that we build our assumptions on as engineers — namely that mathematics engineering can be complete and correct at the same time. You have give up on one of them, which is a pretty uncomforatlbe place to be for most engineers who think ultimately we’ll get there, one small step at a time. But, nothing like that is actually possible.

The last thing I would say is just to again invite you to commit yourself to solving real problems. Look for opportunities - ways you can do that internally, inside your company, inside your communities and bigger. I’ll close with a little anecdote to illustrate that we’re still doing the same work, but with a different impact.

In Boulder we had some huge floods in 2013, and DOJO4 pitched in to help folks rebuild. There were a lot of work parties to shovel shit and mud out of people’s basements. And if I asked one of you folks here, “Hey, do you want to come over to my house and shovel shit? Write java, say?” You would say, “Definitely not.” If I said, “Hey, you’re my friend, my house just got flooded. Will you come over with a bunch of us, listen to music, eat pizza, drink beer and shovel shit?” Then you’d say, “Hey, I’m there! I’ll help you out.”

So, the reason that you’re doing the work matters a great deal. Real impact does start with simple acts of fundamentally being kind. Matz is the greatest example. Look at how small of a thing it was just to say, “Ruby is about being nice; I’m nice.” Look at how many people he impacted through just that statement. Look at the different kinds of software and conversations that are had in the Ruby community versus other communities. It’s quite possible. And that’s it.